Most content on this topic frames it as a binary: build or buy. Custom software on one side, off-the-shelf on the other, with a generic pros-and-cons table in the middle. That framing assumes the reader is a CTO evaluating architecture options. It is not written for a business owner who has spent the last two years building every customer quote in a spreadsheet because no platform can accommodate their product configuration and volume pricing.

The actual question small business owners face is more specific: when off-the-shelf tools don’t fit a specific process and the workarounds have become part of daily operations, is custom software realistic, or should the business keep adapting? Answering that question requires more than a pros-and-cons list. It requires evaluating three things: how central the process is to how the business operates, how well the current tools actually fit, and what the real cost trajectory looks like over time. The decision ultimately reduces to three questions. The sections that follow walk through the logic first, then apply those questions at the end.

Not All Processes Deserve the Same Answer

The biggest mistake in the build-vs-buy conversation is treating a business as a monolith. Not every process warrants the same level of investment, and not every limitation justifies a custom solution. Most businesses have three categories of processes, and each category has a different answer.

Commodity Processes

Commodity processes include things like payroll, email, basic accounting, and file storage. These processes are essentially the same across every business. The workflows are well-understood, the regulatory requirements are standardized, and the off-the-shelf tools that handle them are mature and inexpensive. No small business gains a competitive edge from a better payroll system. The right approach is to find a tool that works at a reasonable price and direct investment elsewhere.

Important but Standard Processes

Important but standard processes include things like customer relationship management, project management, invoicing, and basic inventory. These processes matter to the business, but they are not unique to how it operates. A professional services firm’s project management workflow is broadly similar to other firms in the same industry. The tools available for these processes are generally capable, though fit varies. The right approach is probably to buy, but to evaluate fit carefully before committing. Configuration and minor customization can often close any ill-fitting gaps. If the competitive advantage does not live inside a given process, optimizing it beyond what standard tools allow is rarely worth the capital.

Differentiating Processes

Differentiating processes are the workflows that are specific to how a particular business operates: custom pricing logic that reflects negotiated relationships, multi-warehouse inventory allocation with rules no standard system can express, approval workflows that mirror how decisions actually get made in the organization, quoting processes that combine product configuration with service scheduling in ways that no off-the-shelf tool accommodates, or product catalogs with complex configuration that no standard CMS or e-commerce platform can represent to customers.

Most businesses have one or two processes in this category and many in the first two. The framework starts by identifying which category a given process falls into. If the process is genuinely differentiating, the build-vs-buy question becomes relevant. If it is not, the answer is almost always to buy.

How to Tell When the Tool Is Shaping the Process

When off-the-shelf software fits a process well, employees use it without thinking about it. When it does not fit, specific symptoms appear, and they are remarkably consistent across industries.

The Parallel Spreadsheet

Employees maintain a spreadsheet alongside the official system because the system cannot represent the actual data relationships the business requires. The spreadsheet becomes the real source of truth, and the system becomes a formality that gets updated after the fact (if it gets updated at all). This is one of the clearest indicators that the tool does not match the process.

Duplicate Data Entry

The same information gets entered into multiple systems because those systems do not connect. An order enters the e-commerce platform, then gets manually re-entered into the inventory system, then appears again in the accounting software. Each re-entry introduces delay and the possibility of error, and the labor cost compounds across every transaction.

Institutional Workarounds

The team has developed processes so embedded that new employees learn “how we actually do it” as distinct from “what the system says to do.” When the workaround is more established than the tool’s intended workflow, the tool has stopped serving the process and the process has started serving the tool.

Manual Report Assembly

Reports require exporting data from multiple systems and combining them manually because no single tool has the full operational picture. A business owner who spends Friday afternoons assembling a weekly report from three different exports is not getting visibility from their tools. They are creating it despite their tools.

These symptoms represent what might be called a workaround tax: the ongoing labor cost of adapting human behavior to compensate for tool limitations. This cost is evident but invisible because it is distributed across people and hours rather than appearing on a single invoice. A business with two employees spending five hours per week each on manual data transfer, reconciliation, and workaround maintenance is spending roughly $15,000 to $25,000 per year in labor applied to compensating for tool limitations, depending on those employees’ compensation. That figure never appears in the “low monthly cost” column of the off-the-shelf comparison.

The Cost Comparison Nobody Actually Does

The standard comparison is simple: custom software has a high upfront cost, and off-the-shelf has a low monthly cost. This is technically accurate and practically misleading, because it omits several factors that shift the math significantly over time.

SaaS Pricing Scales with Headcount

A $50 per seat per month tool that costs $500 monthly for a ten-person team costs $750 at fifteen people. Over three years at the larger team size, that is $27,000 for a single subscription that still does not do what the business needs. Per-seat pricing that seems reasonable at current headcount becomes a substantial line item as the business grows, particularly when multiple tools are involved.

The Second and Third Tool

When the primary tool does not cover the full workflow, businesses bolt on additional subscriptions: an email marketing platform because the CRM’s campaign features are insufficient, a document signing service because the invoicing system cannot handle contracts, or a scheduling tool because the project management system has no customer-facing booking capability. Each addition carries its own subscription cost, learning curve, and maintenance overhead. The cost is not additive; it compounds, because each new tool introduces integration complexity with every tool already in the stack. A business running five or six SaaS subscriptions at $50 to $200 per month each is spending $6,000 to $15,000 per year on a patchwork that still requires manual intervention to function as a whole.

The Switching Cost of Waiting

Every year spent adapting to a bad-fit tool builds process debt. Workarounds become institutional. Employees build habits around limitations. Data accumulates in formats that are difficult to migrate: four years of inconsistent naming conventions, hundreds of saved spreadsheet templates that encode business logic nobody documented, and export formats that only make sense to the person who designed them. The eventual switch becomes more expensive each year, not because the new solution costs more, but because there is more to untangle. A business that recognizes the problem in year one and addresses it faces a simpler migration than one that waits until year four.

What Custom Actually Costs

Business owners often assume custom software costs hundreds of thousands of dollars because that is the enterprise price point. For small business operational systems, realistic budgets are often in the $30,000 to $80,000 range for an initial build, with ongoing maintenance typically running $200 to $2,000 per month depending on complexity and required resources. These numbers are not trivial, but they are not the six-figure minimums that enterprise providers require. When compared against the three-year cost of multiple SaaS subscriptions plus the workaround tax, the break-even point often arrives sooner than business owners expect.

When Custom Software Is the Wrong Answer

A framework that always concludes “build custom” is not a framework. It is a sales pitch. Custom software is a meaningful investment, and there are clear situations where it does not make sense.

The Process Is Not a Differentiator

If the way a business handles invoicing is essentially the same as every other business in its industry, QuickBooks is the right answer. Custom invoicing software would be a waste of money. The build question only becomes relevant when the process itself is what makes the business different from its competitors, and when standard tools cannot accommodate that difference.

The Tool Handles 90% of the Need

If the gap between the off-the-shelf tool and the actual process is small, configuration or minor integration work is almost always more cost-effective than a full custom build. A CRM that handles most of a sales workflow but needs a few custom fields or an automated notification is a configuration problem, not a custom software problem.

The Business Does Not Yet Know Its Own Processes

Early-stage businesses whose workflows are still evolving should not lock in custom software around processes that may change significantly. Off-the-shelf tools provide the flexibility to experiment. Custom software makes sense once a business has enough operational history to know how it works and where standard tools fall short. Building custom too early risks investing in a system designed around assumptions that turn out to be wrong.

The Budget Creates Financial Strain

Custom software is an investment, not an expense to absorb passively. If a business cannot fund the build without financial strain, it is better to optimize the workarounds, document the actual requirements, and plan for custom when the economics work. A well-documented set of requirements makes the eventual build faster and more accurate.

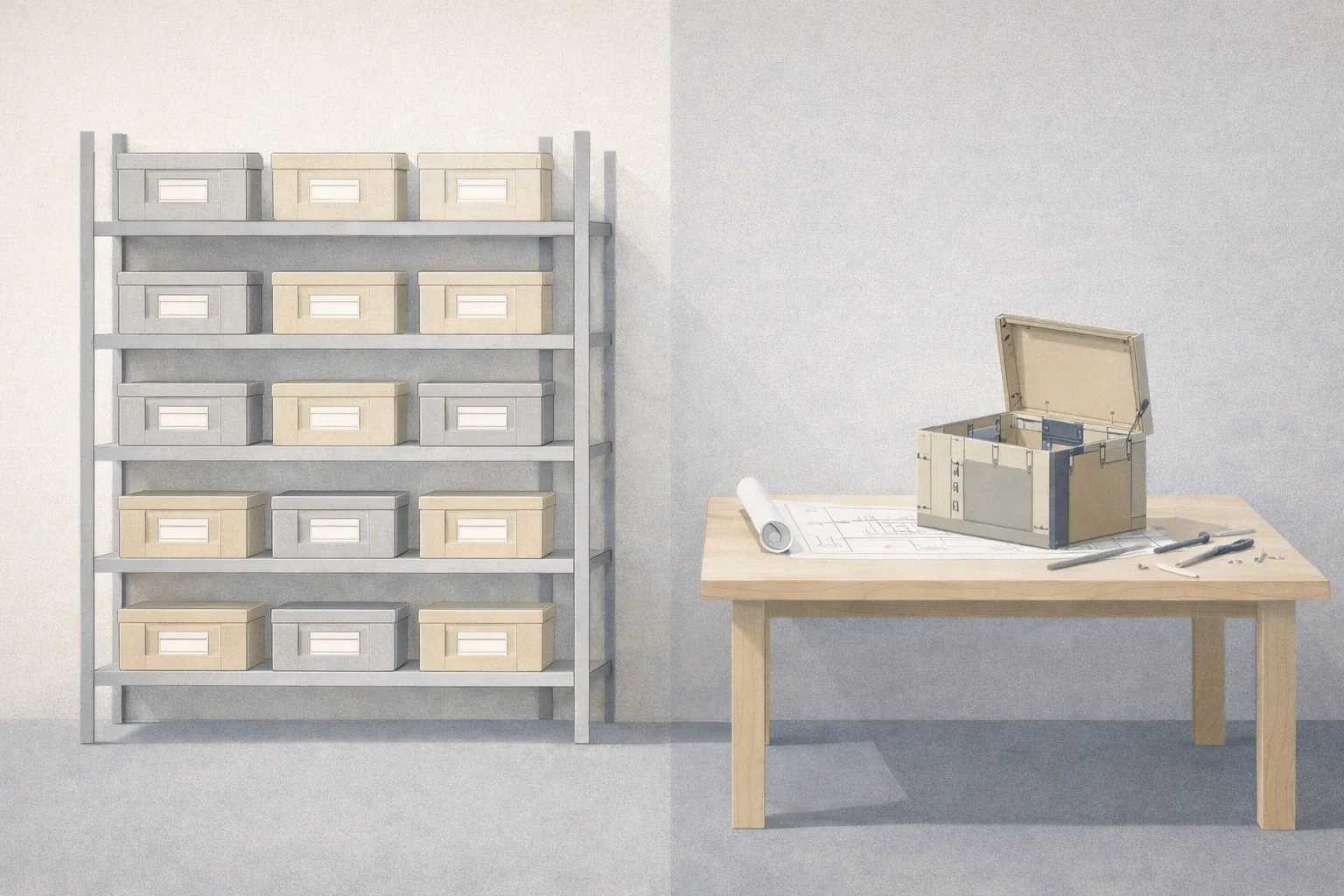

The Hybrid Reality

For most small businesses, the answer is not fully custom or fully off-the-shelf. It is hybrid: standard tools for commodity and standard processes, custom for the one or two differentiating workflows where the business genuinely operates differently.

In practice, this means keeping QuickBooks for accounting, keeping the HR tool that handles payroll, but building a custom system for the specific operational workflow that no off-the-shelf tool handles well. The custom system connects to the standard tools so data flows between them automatically: orders sync to accounting, customer records stay consistent across platforms, and reports pull from a single source of truth rather than requiring manual assembly.

This hybrid approach concentrates the custom investment where it creates the most operational value while avoiding the waste of rebuilding what off-the-shelf tools already handle well. It also means the custom component can be smaller, more focused, and less expensive than a business owner might assume when they hear “custom software.”

The same logic applies to the customer-facing side of a business. A company whose products require interactive configuration, custom data structures, or presentation that no standard CMS can express faces the same build-vs-buy question for its website as it does for its internal systems. When the standard platform cannot represent what the business actually sells, custom web development becomes worth evaluating for the same reasons custom operational software does. The framework does not change; the evaluation is the same regardless of whether the process faces inward or outward.

A Three-Question Framework

The build-vs-buy decision reduces to three questions, applied to each process individually rather than to the business as a whole. Each corresponds directly to the three dimensions discussed above: process type, tool fit, and long-term economics.

Decision Summary by Process Type

| Process Type | Tool Fit | Cost Trajectory | Likely Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity (payroll, email, accounting) | Standard tools fit well | Low and predictable | Buy the cheapest tool that works |

| Important but Standard (CRM, project management, invoicing) | Standard tools fit with configuration | Moderate, scales with headcount | Buy, but evaluate fit carefully |

| Differentiating (custom pricing, unique workflows, specialized operations) | Standard tools require constant workarounds | High and compounding (subscriptions + workaround tax + switching costs) | Evaluate custom at small business scale |

Is this process central to how the business competes? If the process is commodity or standard, buy. If it is genuinely differentiating, custom becomes worth evaluating.

Does the current tool fit the process, or has the process been reshaped to fit the tool? If employees maintain parallel spreadsheets, enter the same data in multiple places, or have developed workarounds that new hires must learn separately, the tool is not fitting the process. The workaround tax is real, even if it does not appear on an invoice.

What does the real cost comparison look like over three to five years? Include SaaS subscription scaling, the cost of additional bolt-on tools, the labor cost of workarounds, and the switching cost that grows each year. Compare that against what a custom build would actually cost at small business scale, not enterprise scale.

Not every process needs custom software, and not every off-the-shelf tool deserves the workarounds it demands. The framework is about distinguishing between the two.